|

History of Nonviolence

|

|

Civil Society and Nonviolence in Korea

Printable Version: Download

as PDF

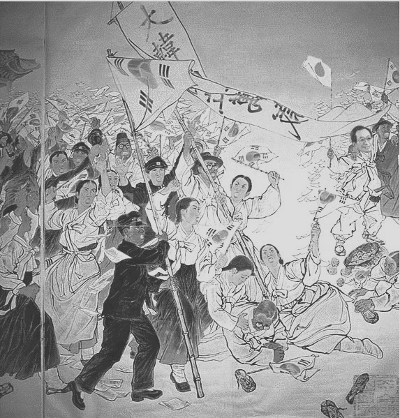

There has been no Martin Luther Kim. There has been no Mahatma Lee. In South Korea, a central figure or symbol of nonviolence has never existed. The government had 'invented' and 'reconstructed' some historical figures as patriots such as Admiral Lee in order to promote nationalism, but an equivalent leader of nonviolence has never emerged. Yet we find numerous examples of nonviolent movements in Korean History. The great Sam-Il movement of 1919 during Japanese colonial rule was one of the largest nonviolent demonstrations in the twentieth century. Korea had been under brutal and cruel Japanese colonial rule since 1910 and leaders of the independence movement engaged in various actions to liberate Korea. It was at the peak of oppression when Woodrow Wilson declared what are known as the "Fourteen Points" in 1918, which outlined national "self-determination." Affected by this idea, Korean students in Tokyo declared their demand for Korean independence. In response, the underground nationalist leaders in Korea decided it was time to act. Organized largely by religious leaders-of Christian, Buddhist, and Cheondogyo (a distinct religion in Korea) leadership-secret plans to hold demonstrations were disseminated throughout towns and villages. At 2 pm on March 1st of 1919, 33 nationalist leaders gathered at Taehwagwan Restaurant in Seoul and read out the Korean Declaration of Independence. The same thing happened in other appointed sites throughout Korea at the same time. Masses assembled and started peaceful demonstrations, shouting out "Daehan-minkuk-manse (Long-live Korean Independence)." It has been estimated that more than one million Korean citizens poured out onto the streets to nonviolently protest against Japanese colonial rule.1 Japanese colonialists responded by sending a police force that attacked, beat, and even shot peaceful demonstrators. Sources count that 7,500 Korean demonstrators were killed and 45,000 arrested. There were sequential demonstrations throughout Korea for about one year and approximately two million Korean people participated in 1,500 demonstrations.2 Although the March 1st movement did not succeed in liberating Korea from Japanese rule - in fact, Japanese rule became even harasher in terms of cultural dominance by forcing Koreans to speak the Japanese language - the campaign became a model for other Asian nations' freedom struggles. It also set the stage for future Korean struggles, and March 1st is still celebrated as a national holiday. Korea's next major nonviolent movement took place in the 1960s, when unarmed students rose up to overthrow the authoritarian regime of Rhee Sung Man. The opposition parties organized thousands of demonstrations that included students and intellectuals, who faced beatings, tear gas, and torture. In 1987, the biggest struggle for democracy in Korea overthrew the authoritarian regime of Chun Du Hwan. Not long after college student Park Jong Chul was tortured and killed by the police, students started engaging in massive street protests. These protests reached a peak on June 26, culminating in the "Great Peace March of the People." Countless demonstrators, including students, white-collar workers, and the middle class, literally packed the streets around Seoul and other urban centers in Korea. The human waves of demonstrators were so overwhelming that the police were running out of tear gas canisters.3 These demonstrations finally resulted in the June 29 Declaration, which ended military rule. According to the "encyclopedia of nonviolent action," the success was made possible by use of violent tactics by the radical front on the one hand and extensive utilization of nonviolent tactics by many students, intellectuals, and members of the middle class on the other hand.4 (Scholars disagree on whether nonviolent and violent action can effectively complement each other. Certain political science professors believe that violent tactics can be helpful when used on the periphery in compliment to nonviolent tactics. However, Prof. Michael Nagler and other peace studies experts say that violence will always contaminate and undermine a movement in the long run and that any substantive achievement of such a movement occurs despite the unhelpful violent components.) This was the beginning of one of the most successful stories of democratization among developing countries in the 20th century. What is even more important is that this was also a significant period for civil society and nonviolence in Korea. After 1987, Korea went through a transition. Rapid industrialization and economic development allowed for the growth of the middle class, which in turn gave rise to Civil Society Movements (mass-based reformist movements against unjust aspects of the capitalist system.). Now that freedom of speech was allowed and a civilian-as opposed to a military-government was in power, the number of civic and voluntary associations rose dramatically. Among these associations were anti-pollution movements, anti-nuclear groups, feminist groups, teachers' associations, journalists' associations, and pressure groups for ensuring responsive state agencies. The growing civil society of Korea at this time also included peasant movements, labor movements, and various other sectoral movements. Koreans have especially focused their activism on environmental issues. In 1991, the government decided to construct a seawall to "reclaim" the land of Saemangum - land reclamation is the creation of new land from foreshore (the part of a beach that is exposed by the low tides and submerged by high tides). This plan was expected to produce economic benefits. However, the nation was divided over the issue and opposition was fierce. Environmental organizations in Korea maintained that loss and destruction of foreshore outweighed any of the claimed benefits - securing farmland, water resources, and preventing flooding in that region.5 In the end, the Supreme Court wrote the final verdict that made it possible to continue the construction. During this 15-year-long debate, there were some extraordinary methods of protest. When the construction was reaching its completion, at 8am on June 12th, 2003, some eighty courageous environmental activists (members of Saemangum Sandbank Solidarity of Life and Peace) snuck into the construction site and started digging up the seawall. (A seawall is a breakwater constructed to block the inflow of water.) Twenty of these activists used shovels and hoes to dig and tear up the seawall, while others chained themselves to build 'human shields.' One activist said, "We came here knowing that this act was illegal. Keep everyone out of here so that it will be peaceful." However, six hours later, at 2pm, some 100 members of Saemangum Promotion Council (which is in favor of the reclamation plan) arrived at the site and started using violence to stop the protests. They beat the activists, kicked them, used water cannons, and even dragged one activist to their boat and committed mob violence. The activists, however, did not resist these egregious acts of violence, saying that they would not harm other human beings. Finally, the leadership of Saemangum Solidarity decided it was too dangerous to continue and withdrew at 5 pm.6 Ultimately, the Saemangum Solidarity protestors were unable to stop the reclamation project, but they did manage to raise public awareness about environmental issues. Fishermen, children, students, and members of the middle class were highly mobilized. One of the protestors' most persuasive actions to reach the hearts of their fellow citizens was a 200-mile march from Saemangum to Seoul. Along the way, they practiced "three-bow, one step," wherein they bowed three times before advacing each step on their path. While the Korean public frowns upon violent activism as a remnant of authoritarian rule and opposition, nonviolent and self-sacrificing demonstrations evoke sympathy with their freshness and deep spiritual meanings. Recently, environmental activists have called to uphold nonviolence not only an ideological principle but as a practical measure and method to create social change. In Korea, nonviolence has 'evolved' without the leadership of a great figure. Nonviolence was used not only to voice people's opinions against repressive regimes, but it is now being utilized in order to bring justice to the environment, society, economy, as well as politics thanks to the awakening and rise of civil society. It can be said that nonviolence has been resurrected and is helping to nurture public consciousness for the cause of environmental protection. We now have a great tool in promoting a more sustainable society.

JyaHyun Lee (Albert) is an international student from Kyunghee University, Korea, studying International Studies.

|

|

|

References: 1. Joungwon Alexander Kim, "Divided

Korea 1969: Consolidating for transition," page 30,

Asian Survey, Vol. 10, No. 1 , A Survey of Asia in 1960:

Part I. (Jan., 1970) |

A

portrait of the memorable Sam-il movement. Approximately

one million or more Korean citizens poured out onto

the streets to nonviolently protest Japanese colonial

rule.

A

portrait of the memorable Sam-il movement. Approximately

one million or more Korean citizens poured out onto

the streets to nonviolently protest Japanese colonial

rule.